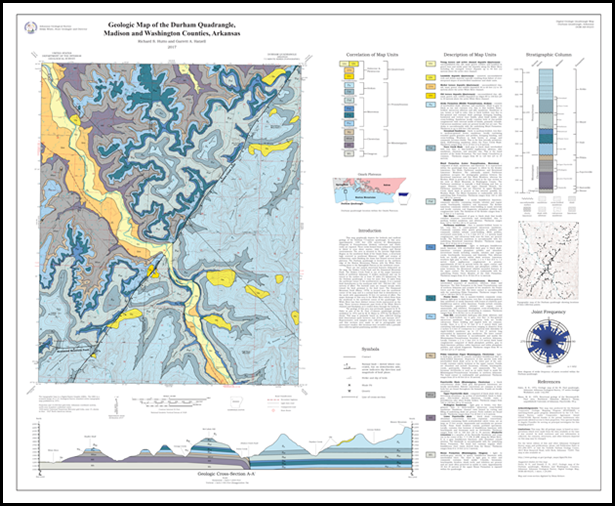

Geologic Map of the Durham Quadrangle, Madison and Washington Counties, Arkansas

Geologic mapping of the Durham 7.5-minute quadrangle in northwest Arkansas was recently completed by the STATEMAP field team. STATEMAP in Arkansas is currently focused on detailed 1:24,000-scale mapping in the Ozark Plateaus Region in north Arkansas. It is accomplished through a cooperative matching-funds grant program administered by the US Geological Survey. Field work was performed between July and February, and included hiking/wading/swimming the entire 12-mile stretch of the upper White River located on the quad. Previous mapping delineated five stratigraphic units for the 1:500,000-scale Geologic Map of Arkansas, but at the 1:24,000 scale, we were able to draw ten. Further division is possible, but several units were considered too thin to map on the available 40-foot contour interval.

You can download your own copy of the map at this link:

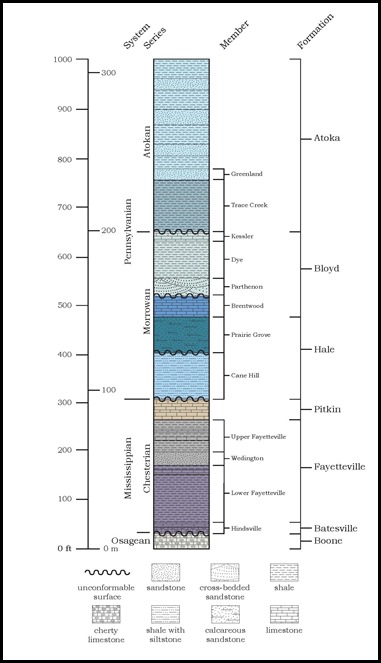

Generalized Stratigraphic Column of Durham Quadrangle

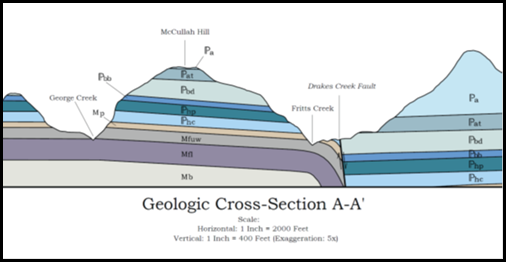

The Drakes Creek Fault, which runs diagonally from the southwest corner to the northeast corner, is the most striking feature on the map. It is part of a major structural feature in northwest Arkansas, forming a lineament that can be traced at the surface for over 45 miles. The Drakes Creek displays normal movement, is downthrown to the southeast, and offsets strata an average of 230 feet. Associated with the fault on the northwest side is a large drag fold. There, rocks parallel to the fault are deformed such that units typically present at higher elevations away from the fault bend down to a much lower elevation next to the fault. Erosion along this side of the fault has exposed the core of the fold along Fritts Creek, Cannon Creek, and other places.

Detail of Cross-section of Durham Quadrangle

The Durham quad is far-removed from areas of previous STATEMAP projects in north Arkansas. We completed work on the Mountain View 1:100,000-scale quad last year, ending on the Brownsville quad near Heber Springs. Focus has now turned to the Fly Gap Mountain 1:100K quad as the next high-priority area. When completed, we will have continuous 1:24K coverage for a large portion of the central Ozark Plateaus Region. The Durham quad was an appropriate choice to begin mapping in this area due to its proximity to designated type sections for many of the formations in north Arkansas. This facilitated easy comparisons between our field observations on Durham with the classic outcrops where these formations were first described. Initial field investigations included locating, describing, and sampling these historic outcrops near Fayetteville. We visited many places the names from which the stratigraphic nomenclature we still employ was derived. These places have such names as: Bloyd Mountain, Kessler Mountain, Lake Wedington, Cane Hill, Prairie Grove, Brentwood, Winslow, and Woolsey. Having seen the stratigraphy in these areas firsthand better prepares us to track changes in lithology and sedimentation as we continue to map to the east and south of Durham in the coming years.

The following images were taken during this year’s field season and are arranged in stratigraphic order from youngest to oldest:

Liesegang boxworks–Greenland Sandstone. Mapped into the Atoka Formation

Asterosoma trace fossils–Trace Creek Shale of the Atoka Formation

Kessler Limestone just below the Morrowan/Atokan Boundary–mapped into the Dye Shale of the Bloyd Formation

Parthenon sandstone resting on the Brentwood Limestone, both of the Bloyd Formation. The Parthenon was also mapped into the Dye

Mounded bioherms in the Brentwood Limestone

Tabulate coral colony in the Brentwood Limestone

Herringbone cross-bedding in calcareous sandstone–Prairie Grove Member of the Hale Formation

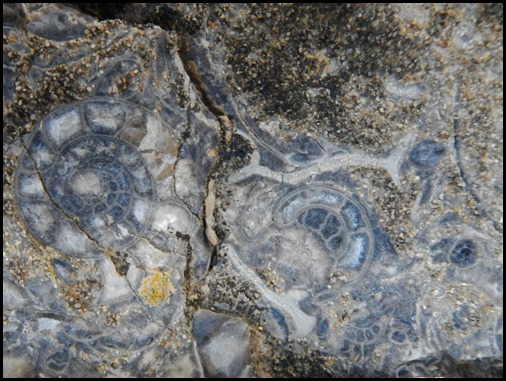

Goniatitic Ammonoids in calcareous sandstone–Prairie Grove

South-dipping sandstone in the White River south of the Drakes Creek Fault–Cane Hill Member of the Hale Formation

Soft-sediment deformation–Cane Hill

Pitkin Limestone, below the Cane Hill near West Fork—Mississippian/Pennsylvanian Boundary

A cluster of solitary Rugose corals–Pitkin Limestone

Wedington Sandstone of the Fayetteville Shale at West Fork

Base of the Wedington–mapped into the upper Fayetteville Shale

Large septarian concretion–lower Fayetteville Shale

Pyritized Holcospermum (seed fern seed-left) and goniatitic ammonoid (right)–lower Fayetteville Shale

Boone Formation, along the White River in the northwest corner of the Durham quadrangle

This year, we’re moving east to map the Japton and Witter quads. Wish us luck as we begin a new field season. We’ll try to keep you apprised, so until next time, we’ll see you in the field!

Richard Hutto and Garry Hatzell